(It is early spring 1761. Charles Huntingdon has returned to London after a few weeks at his new home near Bereton)

On my return

to London I resumed my former lodgings, and reflected that I now had two places

that I considered home. I could have lodged more fashionably now, but I had

grown accustomed to the comfortable old place. My landlady made me most

welcome, whilst at the same time hinting that, in view of my new opulence, an

increase in the rent I paid would not come amiss. I was happy to oblige her.

Next, I made my way to Brown’s club in the

hope of meeting Lord Staines there. I found myself in the midst of an animated

discussion about the continuing war, and noted that a number of the gentlemen

were now in agreement with Sir James Wilbrahim that a swift end should now be

sought to the conflict, for the French fleets would surely not dare to put to

sea again and our new conquests in India and the Americas were secure. Opponents

of this opinion argued that the conflict in Germany was unresolved, where our

ally, Frederick of Prussia, despite receiving millions of British money, was

hard pressed by advancing Russian forces, and it would be dishonourable for

Britain to desert him in his hour of need.

Most

of the gentlemen were troubled by the immense cost of the war, and others

predicted a breakup of the present ministry, where those old enemies Mr Pitt

and the Duke of Newcastle had been obliged to work together only by the

desperate need to save the country. One of the gathering, who was clearly a

curmudgeon by nature, dismissed Pitt as mad and the Duke as a ridiculous old

fool. He predicted that, unless the war was brought speedily to a close, the

country would infallibly sink into a bottomless morass of debt, “And all, sir,

for the sake of the stockjobbers and sugar merchants of the City, and for the

saving of that horrid Electorate of Hanover, that hath for so long preyed on

the very vitals of our poor country!” Sir James Wilbrahim and his friends in

Bereton would surely, I thought, have echoed these sentiments! All, however,

entertained great hopes of our new young King, George III, though little appeared

to be known about him personally.

Lord Staines now entered. He welcomed me

back to the delights of London and described the adventures of our friends

while I had been away, to which I replied with a satirical account of Sir James

Wilbrahim’s dinner party. He then invited me to accompany him to the theatre next

week to see a new comedy that was about to open. He did not remain at the club

long, pleading a pressing engagement elsewhere.

A few days later I was invited to a meeting

with Lord Teesdale. He questioned me, in a detailed but friendly manner,

concerning my time in Bereton, what I thought of the town and my new

neighbours, the condition of my estate, my finances and so forth. He pointed

out that I, as a landowner of importance in the borough, would have much

influence there in the coming general election. I was flattered that he took so

great an interest in me, but confessed that my knowledge of the town and its

people was so far only slight.

I described my meeting with Sir James Wilbrahim

and his friends at Stanegate Hall, and asked if their commitment to the

Jacobite cause might be a danger to the country. He replied that all this was

well known to the ministers:

“I

tell you, sir, in February of 1744, with a French fleet all prepared to invade

these islands, a spy revealed that for every shire there were lists of nobles

and gentry who would rise to fight for the Pretender. The name of Sir James

Wilbrahim was among them. But happily Providence was on side of this fortunate

country, for the French fleet was scattered by storms and the invasion did not

take place. Mr Pelham, who was then Prime Minister, thought it best to take no

action against the traitors, but they knew their names had been pricked out,

and that is why neither Wilbrahim nor any other of the crew came out to fight

for the Scotch rebels the next year.

He then asked, was I aware of what had passed

in Bereton in the great rebellion of 1745? I said that I had been advised not

to ask questions on such matters.

“Wise advice, perhaps,” he conceded, “And no

doubt that there are many there that would wish it was all forgotten. But now

you are a gentleman of importance, there are matters you need to know. For the

rebels reached Bereton at the end of November, on their march south, and were

allowed to lodge there overnight. Not a soul raised a finger against them! Mr

Andrew cannot be blamed, for he was confined to bed with a sickness from which

he never recovered. But as for Wilbrahim: why; he departed for London as the

Scotch army approached! Some said that he fled in fear of having to make a

choice of whether or not to join them. He left his unfortunate lady at home,

all unprotected!

“His

enemies called this the behaviour of a poltroon. But Wilbrahim was not alone in

such behaviour: as I have said, not a single English nobleman or Member of

Parliament came to the support of the rebels. By any consideration, sir; there

were but very few whose love of the Pretender was such that they would lie out

under a hedge in winter for his sake. No, sir: they do little now but drink his

toast whilst deep in their cups, to ‘the king over the water’ or some such

foolishness, and we have nothing to fear from them”.

I mentioned

the Rector, who had seemed so passionate for the Jacobite cause.

“Ah yes, Mr Bunbridge, is it not?” he

replied, “As for him, it was widely believed that he marched on with the rebels

as their chaplain, but when they halted at Derby and turned back, he deserted

the cause in disgust. But nothing was ever proved, and Mr Pelham, as I have

said, thought it best to let sleeping dogs lie rather than waste time and stir

up animosity by pursuing so insignificant an offender. And no doubt he was

correct.

“What use you choose to make of this

history is your concern. You may consider, as many do, that these unfortunate

events are now all safely in the past, for we have new King now who is, like

you, too young to remember them, and from what I hear whispered, many things

may now change. You may consider Sir James Wilbrahim old and foolish, and irreconcilable

in his Jacobitism, but he still wields much influence in and around Bereton,

and furthermore that he has a daughter who will inherit considerable estates; and

so he is well worth cultivating”.

I wondered whether he was suggesting I should

pay court to Miss Louisa Wilbrahim, and only discovered much later how wrong I

was.

He enquired what I had learnt concerning

prospects for the election in Bereton. I replied that Mr Bailey, the other

Member for the town, was not liked by Sir James and his friends, and that they

would prefer that some local gentleman should be found instead. Lord Teesdale

replied that this scarcely came as a surprise to him. He described to me how,

at the last election in 1754, he had persuaded Mrs Andrew and Sir James to act

together despite their political differences and deter any other candidate from

attempting to stand, thereby avoiding the vast expense of a contest. Sir James

had, with some reluctance, acknowledged the good sense of this, and he and Mr

Bailey had in consequence been returned unopposed. I promised to follow my

aunt’s example and give my support to Mr Bailey, as my aunt had done.

I was then asked my opinion on the present

situation of the country. I said that I greatly admired Mr Pitt, and how he had

ensured our glorious victories in the continuing war. He said this was very

true, but the war must soon be brought to an end by some means or other, and

that Pitt and the old Duke of Newcastle were not much liked by His Majesty, and

a prudent man should attach himself to Lord Bute, who was greatly favoured. I remembered

hearing his name mentioned at Lord Teesdale’s dinner party, and asked whether

many gentlemen might not be happy about power being in the hands of a Scotchman,

especially one who, as I understood it, had the misfortune to bear the name of

Stuart, the name of the exiled Jacobite princes. Might it not recall to their

minds the 1745 rebellion that we had just been discussing? Lord Teesdale

replied this was perhaps true, but that His Majesty, like me, was too young to

have any memory of these events, and hoped they could be now buried and

forgotten. I then left, expecting to be invited for further discussions.

Now that spring had arrived, ladies and gentlemen would often visit the Vauxhall gardens in the afternoon, to stroll through avenues of trees and under triumphal arches, listening to hidden orchestras playing and watching the world go by.

I was walking there with George Davies and

John Robertson when the latter suddenly exclaimed, “Hello! What’s happening

here?”

I followed his gaze and observed some

distance away a group of ladies uttering cries of distress. The reason for this

became clear when I saw that one on them had lost her hat, which had blown off

in the wind and caught in the branches of a tree out of reach. It was bright

blue in colour with a splendid ostrich plume: well worth saving, though hardly

suitable for wearing on a windy day. A few bystanders of coarse appearance were

laughing at them.

“I shall fetch a ladder and some workmen,”

Robertson announced, and departed on this mission. It did not take long for

Davies to lose patience.

“Oh, we can settle this ourselves!” he cried,

and turned to me. “Now, Charles: I fancy if you climbed on me, you could

dislodge the hat with your stick. What do you think?” I could scarcely refuse

to make the attempt. I have previously mentioned that he was a veritable

Hercules: quite the tallest and strongest man I have ever met. Now we both

removed our coats and he braced himself, hands on knees, while I clambered up

his back. I sat on his shoulders while he straightened up without any great

effort. He handed me my stick, but despite stretching as far as I could, I was

unable to reach the hat.

“Then you must stand on my shoulders,” he

told me, “I won’t let you fall!”

I did not contemplate the suggestion with

any pleasure, but it was too late to retreat. I placed my right hand, still

holding the stick, on Davies’s head for balance, and my left foot on his

shoulder, where he grasped my ankle firmly. I then paused before straightening

the leg and attempting to grab some twigs, now green with the fresh leaves of

spring, which I could see above me, and which I prayed would bear my weight. I

heard the ladies squeak with alarm and beg me not to endanger myself. A crowd

of men had by now gathered to watch the sport: none offered to help, and

instead I heard bets being offered on whether I might fall. I observed that the

odds on a serious injury were not encouraging.

With a sudden lunge I planted my right foot on

Davies’s shoulder and sprang upright to gasp some twigs, which fortunately held

firm. I followed with my left foot and he grasped my ankles. If my movements

caused Davies some discomfort, he did not show it: I never knew him admit to

suffering any pain. I was now able to reach the hat, and dislodged it with my

stick. It swung in the wind as it fell, and its lady owner sadly failed to

catch it. The spectators all cheered and applauded.

I dropped my stick, but how was I to get

down? George Davies had no doubt. “Jump!” he instructed, “It’s soft grass

below! You won’t hurt yourself!” To encourage me, he let go of my ankles and

gave my legs a push. I fortunately landed on my feet and a lady who was more

alert and braver than the others caught me as I stumbled forwards.

It was at this point that John Robertson

returned, bringing two gardeners carrying a long ladder. “You’re too late!

You’ve missed all the fun!” Davies jeered. “To the heroes, the spoils of

victory!” he added, grasping two ladies round their waists with his huge arms.

They uttered little shrieks of alarm, but offered no resistance. Meanwhile the lady whose hat had been rescued most

ungratefully refused to wear it, saying that it been irretrievably ruined by the

dirt.

I attempted to give proper thanks to the

lady who had saved me from falling, and discovered to my astonishment that she

was none other than Mrs Elizabeth Newstead, whom I had met at Lord Teesdale’s

dinner!

I introduced myself and she affected to

remember me; whether truthfully or not I could not say. She complimented me

very prettily on my courage. I said it was nothing, and acting the young

gallant, I told her how much I had enjoyed her company at the dinner, and that

I would greatly desire a closer acquaintance. She smiled at this and replied

that I was welcome to visit her as often as I pleased, suggesting next Tuesday

afternoon for a meeting.

On Tuesday I accordingly dressed in my best

and waited on her at her home in Pall Mall: not as grand as Teesdale House, but

a very elegant dwelling. She was simply dressed in white silk with a blue

stripe, and a little white cap on her head. A maid served us tea in fine

porcelain cups. Elizabeth explained that she lived there alone because her husband,

Mr David Newstead, a wealthy India merchant, much older than her, was out in

Madras with the great Robert Clive and was not expected to return for many

months. Indeed, she had no means of determining if he was still alive.

The room where we sat was dominated by a

fireplace of mottled marble, carved with swags of fruit and leaves, and a coat

of arms on a shield above.

“Your arms?” I asked.

“Oh no! We lease this house from an Irish

nobleman: Lord Ballybrittas, or some such barbarous name”.

I confessed

that I had never heard of this Lord Ballybrittas.

“Oh, I might have got the name wrong.

Really, I can’t remember! He impoverished himself gambling on the races, and

fled back to his native soil. I never met him. My husband arranged the lease: at

a good price, no doubt. Anyway, those are the Ballybrittas arms. The

construction is not in the best of taste, is it? When my husband returns I

shall ask him to have it removed. Now, if my husband is ever honoured with a

peerage – and I can tell you, he is willing to expend infinite quantities of

Indian gold and silver to that end – I hope he will not permit himself to be

fobbed off with so absurd a title. I would consider it money wasted!”

The largest painting on display was of a

family group in a garden: Elizabeth seated on a bench, an older man, evidently

Mr Newstead, her husband, leaning over her, looking proud and self-satisfied,

and two small boys playing with a large dog. A female servant in Indian dress

knelt at the side.

“Devis painted it a few years ago”,

Elizabeth told me, “It is very like us. But we shall have Reynolds paint

portraits of us now that the boys are older”.

I commented on how handsome her sons were,

which pleased her greatly.

“Oh yes!” she said, “But now they are

away at school, and I miss them so much!”

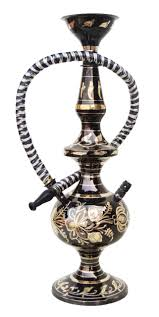

She then showed me some of the curious items her husband had sent her: much silver, richly embroidered fabrics, elephants and tigers carved from ivory and curious pagan idols with gemstones for eyes. Some had several arms, and one had the trunk of an elephant. In one corner of the room there stood a vast object of silver and brass, elaborately decorated, with a long tube attached.

“That is my husband’s hookah,” she told me,

“He smokes it constantly. Sometimes I think he would sooner be parted from me

than parted from his hookah.”

She next drew my attention to a sort of little pipe; unlike any pipe I had ever seen before.

"And this is for my husband’s opium,” she

explained. “Sometimes he smokes the drug, and sometimes he eats it. I do not

like the habit. But he suffers from afflictions which convulse him great pains

that he says only opium can relieve.

“Such are the perils of the East. He told me

that he was one of half a dozen adventurous young souls, scarcely more than

boys, who embarked to India together to seek their fortunes, but within a few

years all but him were dead or entirely broken in health. I would not wish my

sons ever to set foot there!”

She complained that with her husband

away in India and her sons at school, she was alone, save when she was invited

out by her friends. I said that I would always be delighted to visit her, if

she would wish for my company, and would take great pleasure in escorting her to places where it was not considered proper for ladies visit on

their own. I expressed my surprise

that she had attended Lord Teesdale’s house withot an escort. She replied that this

was because she had long been a friend of the Countess, who had particularly

asked her to come, and that happily I was there to take her in to dinner. I did

wonder whether I had been invited solely for that purpose, but did not say so:

instead I gallantly replied that in that case it was a great good fortune for

me.

Elizabeth quizzed me about my family and my

childhood, but I told her there was little to be said. My father had been a

vicar in a remote country parish, and I had no brothers or sisters. Both my

parents had died when I was young, leaving me barely enough to pay a woman in

the village to house me. That I was able to proceed to school and then to

Cambridge was due to the benevolence of Mrs Andrew, to whom alone I owed my

present prosperity. Elizabeth laughed and said, “Then you are truly a man

without a past! I know some who would envy you that!

“As for myself”, she added, with a sigh, “I have too much of a past!”

I might have asked her to explain this comment, but instead I told Elizabeth how Lord Teesdale had described for me the great peril of the Jacobite revolt, and asked Elizabeth whether she had been in London at that time.

“Indeed I was, and I remember it well!” she replied, “I was newly married, and my husband was hard at work in the offices of the East India Company. He took me out to see the soldiers marching to their camp at Finchley, and I thought they made a very poor show. I was most fearful for our future, for the whole city was in turmoil, what with stories of a huge number of the Scotch bearing down on us, and a French landing expected daily and all our best troops away fighting in Flanders. But then a few days later, we heard that the rebels had turned back at Derby and were retreating to Scotland, and the French never invaded, so all was well again."

“Mind you,” she added, “Lord Teesdale’s

conduct at that time could never be called heroic. Indeed, he sat tight,

pleading illness, until it became clear which side was winning, and finding

that it was not the Pretender, he proclaimed King George with all his might,

and raised a militia to fight against the Scotch – who by that time were back

in Glasgow, of course!” She chuckled at the memory.

“I did not go to watch Lord Lovat beheaded

as a traitor on Tower Hill in 1747, for my husband feared that the experience

would be injurious to my health. But I was never as weak as that! Events, though, proved

him to be right, for an immense stand that had been erected to hold the

spectators suddenly collapsed, and many were injured. It was no more than they

deserved!" She chuckled again, this time scornfully.

At the conclusion of my visit, I kissed her

hand and promised to return on Friday.

On Friday the weather fortunately was warm and Elizabeth was eager to venture forth. I was proud and delighted to be

seen in her company, though because of her fine dresses and delicate shoes, and

an enormous hat bedecked with a mass of white feathers, she absolutely refused

to walk any distance on the dirty streets, but insisted on being conveyed in a

sedan chair, while I walked beside her making conversation. It was not

surprising that she hated living in the country.

Our path was eastwards to the city. As we

walked, Elizabeth described how greatly the capital had changed since she first

came to live there. London bridge had been lined with shops, now demolished;

the bridge between Westminster and was new, and now another was being planned

at Blackfriars. The streets were becoming cleaner, with more regulations on

paving and drains and sewers, and no longer were great herds of cattle

driven across Oxford Street to be slaughtered at Smithfield. “All of this to the

great benefit of our shoes!” she laughed.

Eventually we reached Cock Lane, in the City, which Elizabeth, I found, had long wished to visit. It was said that the ghost of a woman, thought to have been murdered, communicated with a young servant girl by means of scratches on a wall, which were then interpreted for the enlightenment of the public. We found a vast concourse of persons of all ranks there, with the child lying on a bed in a wretched chamber lit only by a dim rushlight. Two Methodist clergymen attended her, and explained the phenomenon to visitors. Their pompous and unpleasant manner irritated us. I replied politely to them, which proved to be a mistake, for they marked me down as a likely convert and insisted on giving me their pamphlets. Elizabeth and I later read these, which she dismissed as scribblings, and said she had not the least desire to listen to long ranting sermons about the dire state of her soul. Thereby she found herself in agreement with Rector Bunbridge, though I suspected Mr Chamberlain might have felt differently.

Elizabeth was convinced of

the truth of the ghost (as, I was told, was the great Doctor Johnson), but I

remained sceptical, suspecting a gross fraud was being practised upon the

public. In the end I was to be proved right, and the poet Mr Charles Churchill,

whom I was to meet later, wrote a most amusing satire about the Ghost.

We then returned home by way of Covent Garden and the Strand, where

we passed what seemed like an eternity inspecting the shops. I considered

buying a present for Louisa Wilbrahim, but found myself devoid of inspiration,

and instead purchased a few pretty trinkets for Elizabeth, thereby increasing my

debts. But my patience was rewarded when we eventually took tea, and, greatly

to my surprise, she began to confide in me.

She told me more about her husband. David

Newstead, I learnt, was born in Norfolk, where through the assistance of his

parish vicar and the squire he had been able to obtain a post as a writer in

the East India Company, at just £5 a year, and had departed for Madras. Many

years later he returned, very rich and with pockets full of gemstones, and he then courted and married Elizabeth. Her parents were Yorkshire gentry, by name Armitage; of

ancient lineage but much reduced in wealth. They considered

Newstead’s background plebeian and manners coarse and unrefined, but they could

not deny his gold.

“Why he chose me for a wife, I really have

no idea. I was pretty, certainly, and I brought with me some property. There

was on our land the ruins of an abbey, dissolved by Henry the Eighth, which

provided a delightful prospect, but I doubt if it was this that won his love.

He would have been more interested by the belief that seams of coal lay beneath

it, though so far none had been found. His courtship of me, when he was not

counting the gold in his purse, was to talk endlessly about India; about the

heat and the strange trees and the great pagan temples and the opportunities

for gaining wealth through trading. I was a very young girl and knew little of

life, so I found it fascinating; though when I came to find that he had no

other conversation I found it unutterably tedious. But I cannot complain

overmuch, for now I am rich, and he is seldom here, and so I am free to enjoy

my own life!”

I asked her whether her husband had been on

the famous raid to Arcot in 1751, which had first established Mr Clive’s reputation

as a great commander. She replied, with a light laugh, that she did not know

where Arcot was, and that she had no intention of finding out. And now her

husband was back in India once more, where Mr Clive was leading British forces

to victory in Bengal and no doubt lavishly enriching himself and his followers.

“If my husband lives," she said, “He will

doubtless return with more gold and jewels than ever!"

I was not a little

shocked that she appeared to take her husband’s survival so lightly, and this

must have shown in my face, for she now embarked on a most astonishing

discourse.

“Oh, I doubt if he ever cared much for me at

all. I think he cares for our sons, though he seldom sees them, but for me …. I

am certain he keeps a mistress in London when he returns here, and out in

India, who can tell? There could well be a score or more of coffee-coloured

brats who would claim him as their father! He had always kept me well supplied

with money, for it would shame him if I was left in poverty, and he sends me

costly presents from time to time, but …. Let me show you this!”

She unlocked a drawer to show me a necklace

of silver and pearls, from which was suspended an immense blood-red stone the

size of a quail’s egg. I was amazed.

“He gave me this when our first son was

born,"

“Why did you not wear it at Teesdale House?”

I asked.

“Help me put it on and I will show you why

not!”

At her direction I fastened the tiny clasp

behind her neck and stood back as she turned to face me. The great ruby hung

down over her bosom.

“You see? The colour does nor suit me at

all. If he knew me at all, he would have known that I never

wear red! I only wear it when I am with him, because he would expect it.”

I said that I was no judge of colours, but

agreed that it did look strange, when contrasted with the blue of her eyes.

“If he knew me, he would had given me

sapphires!” she sighed, as I removed the necklace and she returned it to its

drawer.

I once more kissed

her hand, and hoped to kiss more of her in the future.

The

new comedy that Lord Staines and I attended proved to be a poor affair: the

audience greeted it with jeers and abuse throughout and it closed after a few

performances. I would not have remembered the evening at all but for an

incident after we had left the theatre. The district around Drury Lane includes

a tangle of foul alleyways and courts which no wise man would enter even during

the day, and as we passed the entry to one of these a party of ragged men

issued forth against us, intent on robbery or murder. I feared the worst, but

Staines pulled me with our backs to a wall, drew his sword and signalled to me

to do the same. His face was set firm and there was a cold, fearless look to

his eye, as befitted an officer who had witnessed death on the battlefields of

Germany. I did my best to hold a steady blade, whilst reflecting that our

swords were really little better than toys, which could easily be beaten down

or broken, and that I had no idea of how to use mine, never having had a

fencing lesson in my life. Fortunately our defiance caused our assailants to

halt and content themselves with uttering oaths and threats, and when, after

what seemed like an age, another party of theatre-goers appeared, they

retreated back to their evil warren.

Lord Staines congratulated me on my

steadfastness and then, greatly to my astonishment now embraced me warmly and

kissed me. I wondered whether he had in reality been more frightened than he

had appeared. He next invited me, should I feel exhausted after our adventure,

to come to his home to rest and refreshment; but being caught by surprise, I

declined the invitation, and made my own way alone to my lodgings, where I

quickly fell asleep.

The next time I called on Teesdale House I found the Earl in a corner of the library contemplating a picture I had not previously noticed. There was a boy standing in a meadow, with in the background some buildings. The boy wore a red coat and white breeches, and carried a long, curved cricket bat over his shoulder. Examining his face, I thought I could detect a family resemblance, so I asked, “That is Lord Staines, I presume?”

(A young cricketer)

I was most surprised at the reaction this remark produced. “No, sir, that is not Staines!” Lord Teesdale announced, in a most strange voice that suggested a conflict between rage and despair. He did not turn to face me, but kept his eyes fixed on the painting. Caught unawares by this response, I began to recount Lord Staines’s courageous behaviour outside the theatre, but was interrupted by Lord Teesdale smacking his hand down on a pile of papers on the table and exclaiming, “More debts! And he expects me to pay them! Disgraceful! I can only pray that his mother never learns of his conduct!”

I replied, rather weakly, that I had never

known Staines do anything that was grossly wrong, but his father swept that

aside.

“If you mean that he does not run after

whores like the rest of you young men, then no doubt that is true; though there

are times when I almost wish he would!” He then waved me to go away, and I

retreated in confusion.

What should I learn from this astonishing outburst, so very different from my previous experiences of Lord Teesdale’s character? I would have to ask Elizabeth Newstead for an explanation next time I saw her!

No comments:

Post a Comment